“Why the long face?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Curtis replied. “I mean, I know why I have a long face, I just don’t know what to do about it?”

“Tell me more?”

“I have a guy in a project manager role, that I believe is over his head. Most things, he does okay, but there are times when he falls short, and I have to come to the rescue. That’s not so bad, but he is just so arrogant when things don’t go as they should.”

“What do you mean, arrogant?” I pressed.

“Well, let’s say the project is rolling along, we are about 80 percent finished, he seems to just drop the ball, like the project is finished. But the last part of project is where all the problems are. Lingering details that if they don’t get buttoned up, the project drags past the deadline. The client gets upset. We can’t send an invoice, because there are still outstanding items. We may have even pulled the crew off the job and then find out there are still incomplete issues hanging out there.”

“I thought you said the problem was arrogance?”

“That’s what I mean. The client calls me, usually hot under the collar. I confront the project manager and he starts blaming all kinds of people for things he should have under control. He acts like following up on those last few details are beneath him, that he can’t be bothered. Sometimes, he even says the client shouldn’t be so upset over something so minor, that the client should be glad that we did such a good job on the rest of the project. Then he complains that the work crew should have picked up those details and that if we would just hire better people, then I would be able to see just what a good project manager he is. When he is talking like this, he gets loud, insistent, just plain arrogant.”

“Tell me,” I nodded, “is this project manager effective on the projects you have assigned to him? Can he make the grade, based on his performance?”

“No,” Curtis explained. “On smaller projects he does okay, but these longer projects, he falls short.”

“If your project manager can’t make the grade, based on his performance, then how does he survive on your team?”

Curtis began to shake his head. “You are right, he survives, because I hate to confront him. Sometimes, I even cover for him with the client, just so I don’t have to talk to him. He becomes arrogant, so I won’t talk to him, that’s how he survives.”

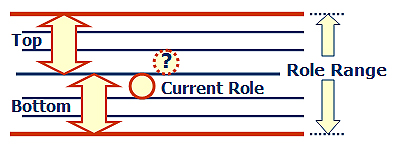

“So, he engages in arrogant behavior because he is mis-matched in a role that is over his head. Instinctively, he knows. Instinctively, he tries to survive as best he can. Arrogance has probably worked for him in this circumstance, most of his life, so, as a coping behavior, he can survive. Who put him in this role?”

Curtis smiled. “I did.” Several seconds elapsed before he continued. “I guess I am the one that has to fix this.”

“I believe so. You are the manager. What is your plan? What do you think you will do? What will be your first step?”