“I was one of the guys, as the team supervisor, now I am their manager,” said Jeremy. “I mean, I know what to do, it just feels weird.”

“Tell me about it.” I asked.

“Well, on Friday, we used to always go out for happy hour. Now, I am holding back. Maybe I will show up once a month after work, but I will usually only stay for one beer, then I beg off and hit the road.”

“What’s changed about the relationships?”

Jeremy took his time to respond. “I guess, instead of being a friend, the relationship was always about the work. I mean, it’s okay to be friendly, but sometimes you have to hold the line, sometimes you have to confront, sometimes the conversation is difficult.” He stopped. “And sometimes you feel by yourself.”

“So, who can you hang out with now?”

“Well, there other managers in the company. They have all been supportive. It is a different perspective. I’m the new kid on the block.”

“And what about your old team, from when you were a supervisor?”

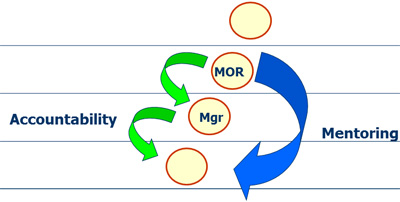

“I am still a manager in that department, but now I work through their new supervisor. My relationship with the team, it’s not accountability anymore, not with me. Now, it’s more like a mentor relationship. It’s a longer view. Instead of me, telling them what to do, I do more observing. Their new supervisor is more concerned with their day-to-day productivity. I am actually looking for the team member that will emerge as the next supervisor in another year.”

“Why do you think all this feels weird?” I ask.

“It’s new,” said Jeremy. “My role is different. I never thought there was this much difference between being a supervisor and being a manager.”

_____

Our online program, Hiring Talent, kicked off its orientation last Friday, but there is still time to jump in on this round. For more information and registration, follow this link, Hiring Talent-2013.