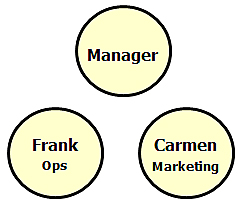

Cross-Functional roles define those working relationships between team members, neither of whom, is the other’s manager. This circumstance most often exists in project teams of short duration and where team members participate on more than one project at the same time.

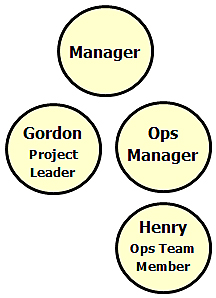

The role of the Prescriber is often associated with the Project Leader and has broad authority to prescribe work to be completed within the scope of the project.

“Gordon, I asked you to this meeting today, with Henry, to talk about your role as Project Leader for the Rising Sun Project that kicks off in three weeks. As the Project Leader, I know you are already deep in the planning phase and looking to get things started.

“To help you in the project, I have borrowed Henry, a team member from our Operations group. Since the project is slated for completion in a three month window, your project team is temporary and Henry still has additional duties outside the scope of this project. I estimate that he will be able to devote approximately 80 percent of his time to you.

“As the Project Leader, you will be assigning tasks for Henry to work on. Because this is your project, you can assign, stop, delay or reschedule any task associated with this project and Henry will do his best to accommodate.

“Regarding the sequence or any process on this project, you have the authority to determine the order or method. If Henry has a question about any of his work, or disagrees with how it should be done, I expect you to sit down and explain the project guidelines. Give it your best shot, but if there is still disagreement, you win. You are the Project Leader and ultimately, it is your accountability.

“Henry, we have assigned you to Rising Sun Project because of the good work you did on your last project. We think you will do well on this project. We expect you to do your best, bringing your talents to this project. Because you have experience in this area, there may be a time when you disagree with a work instruction or sequence. This is Gordon’s project, so I expect you to listen to his explanation and direction with an open mind. At the end of the day, though, this is Gordon’s project, so his decisions stick.

“Henry, you also will remain responsible for some of your operational work. I expect you to devote approximately 20 percent of your time to those tasks. Your Ops Manager is still your manager, for those tasks and any scheduling conflicts. Your Ops Manager will keep Gordon informed on your scheduled priorities two weeks in advance. If Gordon needs more of your time for a specific task, he will talk with your Ops Manager to make arrangements.

“Gordon, if there are any difficulties with this assignment, please work it out with Henry’s manager. Henry’s manager is aware of the priorities in the Rising Sun Project and has agreed to this.”

The Prescriber is given broad authority in this relationship, but the Prescriber is NOT the team member’s manager. The Prescriber is only assigning tasks within the authority of this project.

Should the project become permanent, or where the team becomes permanent, the Cross-Functional relationship may be reconsidered. If the Prescriber has capability one stratum above the team member and the team member is working exclusively under the Prescriber’s direction on a full-time basis, the relationship may be re-defined as a Managerial relationship (rather than a Cross-Functional relationship).

___

Our next online program – Hiring Talent is scheduled to kick off August 1, 2011. If you would like to find out more about the program or pre-register, follow this link.