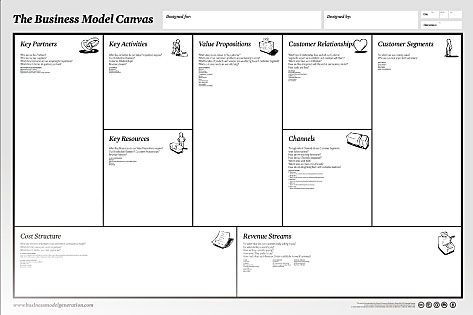

In my previous post, Structure for Strategic Planning, I outlined a concept called the Business Model Canvas, from a project compiled by Alexander Osterwalder. This process contains three steps.

- Document the CURRENT Business Model (using the Business Model Canvas)

- Identify and document external trends that will impact your Business Model

- Create the FUTURE Business Model (using the Business Model Canvas) focusing on those elements you have to change in response to those external trends.

While there are nine elements in the Business Model Canvas, they can be grouped into four categories that are useful for Steps 2 and 3.

1 – Resources

- Key Partners

- Key Resources

- Key Activities

2 – Value Proposition

- Value Proposition (aka USP, Unique Selling Proposition)

3 – Customer

- Customer Segments

- Customer Relationships

- Customer Channels

4 – Financial

- Cost Structure

- Revenue Streams

These groupings are helpful specifically in identifying external trends that will have impact on your Business Model. Here are some questions –

Resources

What is the financial condition of your Key Partners?

What is the flexibility of your Key Partners?

What could disrupt your Value Chain?

What could impact internal teams?

What regulations could change the availability or the way we use our resources?

Value Proposition

What will change about our competitor’s Value Proposition?

How will technology impact our Value Proposition?

What new competitors will enter our market?

What will change about our customers expectations? Demands?

Customer

What could change the financial position of our customers?

What could change the way our customer uses our products or services?

What demographic trends will impact our market?

Finance

What will change about our cost structure? Higher prices? Deflation?

What will change related to personnel costs?

What will change in our regulatory environment?

What will change about our price points related to our cost structure?

What will change about the way our customer purchases our product or service?

Is there a different way to derive revenue from our Value Proposition?

There are a hundred other questions, but this will get you started on this second important step.