From the Ask Tom Mailbag:

Question:

Can you describe the difference between a Stratum II Supervisor and a Stratum III Manager related to their roles and accountabilities?

Response:

Every company and every business model is different, so there will be small differences when you look inside your own company. But let’s look at some generalizations which you can adapt to your specific situation.

Quite often, I use a manufacturing model as an illustration, because most people can identify with these descriptions.

Stratum I – Production, using equipment, tools and machines. The direct output in this Stratum is typically what your customer experiences as your product or service.

Stratum II – Makes sure production gets done. This role is highly engaged in coordinating all of the elements required for production. This includes the scheduling of Production personnel, materials required and machine time (equipment availability or other resource allocation). This role begins by translating customer demand or work orders into specific output targets for production, managing the pace of that production and counting the direct output to make sure production gets done.

Stratum II is also typically responsible for meeting the quality specification in the production process. This may include internal inspection, making measurements to confirm the product or service meets the standard specified by the customer. Where tolerances are critical, additional quality inspections may be performed by an external team, but the resolution for any discrepancy will likely include the participation of the Stratum II Supervisor.

Finally, Stratum II is also responsible for the maintenance of all internal systems, including preventive maintenance on machines, care and storage of tools, inventory and handling of raw materials and finished goods. The most important internal system is often the people system. It is the role of Stratum II to maintain productive relationships with each team member to promote communication about production problems, quality issues, pacing issues and to gather data about the efficiency of the production system.

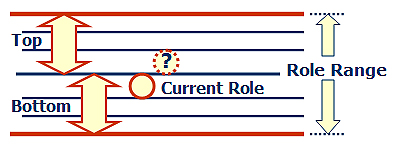

Stratum III – Creates the system. It is the role of Stratum III to map out the production work flow, to analyze the sequence of steps, to monitor the effectiveness of the systems, and most importantly to change the system design to promote efficiency, profitability. This role includes the replacement of capital equipment through life cycles, managing budgets related to production, introduction of new technology and training programs.

The success of the role at Stratum III requires close collaboration with the Stratum II supervisor, to gather data (counting output, counting discrepancies etc) related to the current production system, and to implement changes to the system going forward. Stratum II is often the valuable conduit to collect input from the production team related to the workability of specific processes and sequences.

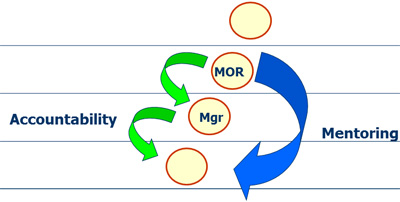

A critical role of the Stratum III manager is in the hiring process. Stratum III is responsible for creating the specific roles in the production team, evaluating the necessity and requirements of those roles. In the hiring of production personnel at Stratum I, Stratum III plays the role of the Manager Once Removed (MOR). This role promotes rich conversations with the Stratum II Supervisor (the Hiring Manager) related to the hiring strategy, protocol and selection.

This short description can be adapted to other business models, using Time Span to calibrate the roles. In some business models, production may occur as a result of teams playing Stratum II, III or IV roles. This will require an adjustment of those roles required to make sure production gets done and roles required to create the systems in which people work.