It’s not too late to join the group in our next Hiring Talent online program. The Orientation begins next Monday, August 1, 2011, so sign up now.

How long is the program? This program will take eight weeks beginning August 1, 2011.

How do people participate in the program? This is an online program conducted by Tom Foster. Participants will be responsible for online assignments and participating in online facilitated discussion groups with other participants. This online platform is highly interactive. Participants will be interacting with Tom Foster and other participants as they work through this program.

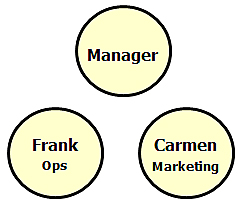

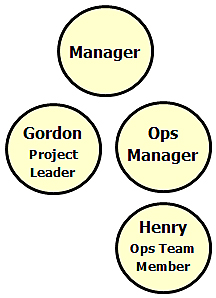

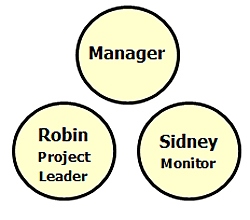

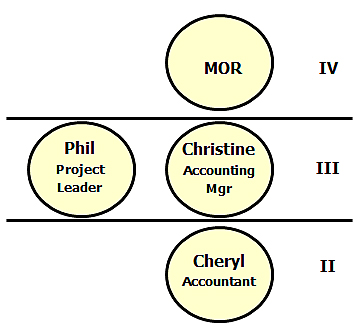

Who should participate? This program is designed for Stratum III and Stratum IV managers and HR managers who play active roles in the recruiting process for their organizations.

What is the cost? The program investment is $699 per participant.

When is the program scheduled? Registration is now open. The program will start, following the registration period, with the Orientation kicking off Monday, August 1, 2011.

How much time is required to participate in this program? Participants should reserve approximately 2 hours per week. This program is designed so participants can complete the Field Work and posting assignments on their own schedule anytime during each week’s assignment period.

Mon, Aug 1, 2011 – Week One

Orientation

Mon, Aug 8, 2011 – Week Two – Role Descriptions – It’s All About the Work

What we are up against

Specific challenges in the process

Problems in the process

Defining the overall process

Introduction to the Role Description

Organizing the Role Description

Defining Tasks

Defining Goals

Identifying Time Span

Mon, Aug 15, 2011 – Week Three

Publish and critique role descriptions

Mon, Aug 22, 2011 – Week Four – Interviewing for Future Behavior

Creating effective interview questions

General characteristics of effective questions

How to develop effective questions

How to interview for attitudes and non-behavioral elements

How to interview for Time Span

Assignment – Create a battery of interview questions for the specific role description

Mon, Aug 29, 2011 – Week Five

Publish and critique battery of interview questions

Mon, Sep 5, 2011 – Week Six – Conducting the Interview (Yes, we know it’s a holiday)

Organizing the interview process

Taking Notes during the process

Telephone Screening

Conducting the telephone interview

Conducting the face-to-face interview

Working with an interview team

Compiling the interview data into a Decision Matrix

Background Checks, Reference Checks

Behavioral Assessments

Drug Testing

Assignment – Conduct a face-to-face interview

Mon, Sep 12, 2011 – Week Seven

Publish and critique results of interview process

Mon, Sep 19, 2011 – Week Eight

Using Profile Assessments