From the Ask Tom mailbag –

Question:

I attended one of your workshops last year and your email is my daily dose of wisdom. Is it the job of the Manager-Once-Removed to step in when he sees an employee’s manager making a mistake. Should the employee be able to go to the Manager-Once-Removed if they believe that their manager is incorrect?

Response:

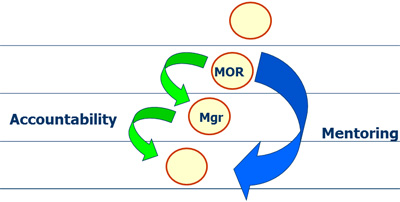

Many companies are so afraid of undermining authority, that they forbid contact between the Manager-Once-Removed (MOR) and team members two strata below. This is actually a necessary managerial relationship. But it’s different.

Let’s tackle the first issue, this undermining authority business. The problem is in the way we frame our assumption. We assume the team member is accountable for their output under the authority of the Manager.

Stop. We missed where the accountability lies.

It is the Manager who is accountable for the output of the team member.

So, while the work of the Manager is to create work instructions for team members, it is also the work of the Manager to ensure those work instructions will be effective in reaching the goal, the task objective. It is imperative for the Manager to constantly ask questions, of the team members, about the effectiveness of the work instructions. It’s part of the role.

This same accountability works one strata above, as well. Who do I hold accountable for the Manager doing a good job of creating and testing work instructions? That would be the Manager-Once-Removed. So, it is incumbent on the MOR to visit the Manager, review work instructions, ask about the effectiveness of the work instructions in the reality of production.

It is also incumbent on the MOR to visit the production area and ask questions, because I hold the MOR accountable for the effectiveness of the Manager.

It is the role of both the MOR and Manager to bring value to the work, decision making and problem solving, of each team member. They are both accountable for the direct output of those team members one stratum below. This is done most effectively by asking questions and listening.