From the Ask Tom mailbag –

Question:

I understand the concept of Time Span as it relates to a manufacturing environment, based on the the examples you used in your workshop. Our company is a software company, we write code, software as a service based in the cloud. Having trouble translating Time Span to this model.

Response:

The first piece of translation is to calibrate your production activity. In a manufacturing environment, production (individual direct output) is most often calibrated as a Stratum I role (Time Span tasks – 1 day-3 months).

Software programming (production of software code) requires a higher level of capability. Task assignments to write code that produce specific software functions, appear to fall within a short Time Span. A coding project might take two weeks to construct, code, de-bug, and test. Seems like a short Time Span task. But in the role of a programmer, the longest Time Span task (which calibrates the complexity of the role) may have less to do with programming and more to do with learning.

I often ask programmers, if you stopped learning about new routines, new programming objects, how long would your code be effectively written, current with the state of the art. The joking response is five minutes, but the real answer is somewhere between three months and one year. It’s not that their published code would stop working, but there are more efficient routines and ways of manipulating code invented every day. Time frame to obsolescence is somewhere between three months and one year.

A good example of this is the move to HTML 5. HTML 5 solves the current dilemma in the way video is handled on the internet, particularly with mobile computing, in a dispute between Apple and Adobe. Adobe would like all video to be handled using its Flash player, Apple says HTML 5 makes the flash player obsolete (and refuses to support it in their iPad and iPhone products). It will take some time for adoption of HTML 5, but programmers are having to learn its new routines. A year from now, programming code that ignores HTML 5 will still work, but fall short of generally accepted programming standards. So, the longest Time Span task, for a programmer, is not necessarily producing code, but continuously learning about new developments in code construction, requires minimum Stratum II capability (cumulative processing).

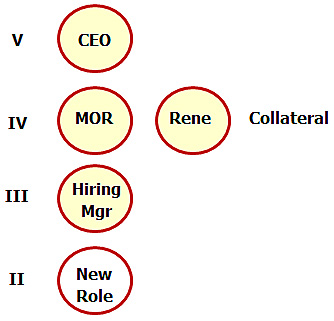

But writing code is not the whole story. A simple stand-alone function is useless. Software typically contains hundreds of functions collected together in a system that creates value for the user. Stringing those functions together requires Stratum III capability, a serial state of thinking. So, you may have programmers, but somewhere in your personnel mix, you will have a manager, also likely a skilled programmer, who decides how the functions are put together.

But a software system is not the whole story. Software systems, to be truly valuable are integrated with other software systems, with interoperability hooks, not only among internal software systems, but external software systems, like Facebook and Twitter. This integration will likely require a manager with Stratum IV (parallel processing) capability.

All of this discussion centers around production. Software companies have other disciplines which must also be integrated, like sales and customer service. Effectively integrating those systems into the mix requires Stratum IV and Stratum V capability.

Levels of work

Stratum IV – Parallel processing

Stratum III – Serial processing

Stratum II – Cumulative processing

Stratum I – Declarative processing